I recently rewatched all the Harry Potter movies. All of them. Eight films, many hours, several regrettable snacks. The movies are fine. Some child acting is… well, let’s call it earnest. Hogwarts remains the only school where trauma therapy is not part of the curriculum. All normal.

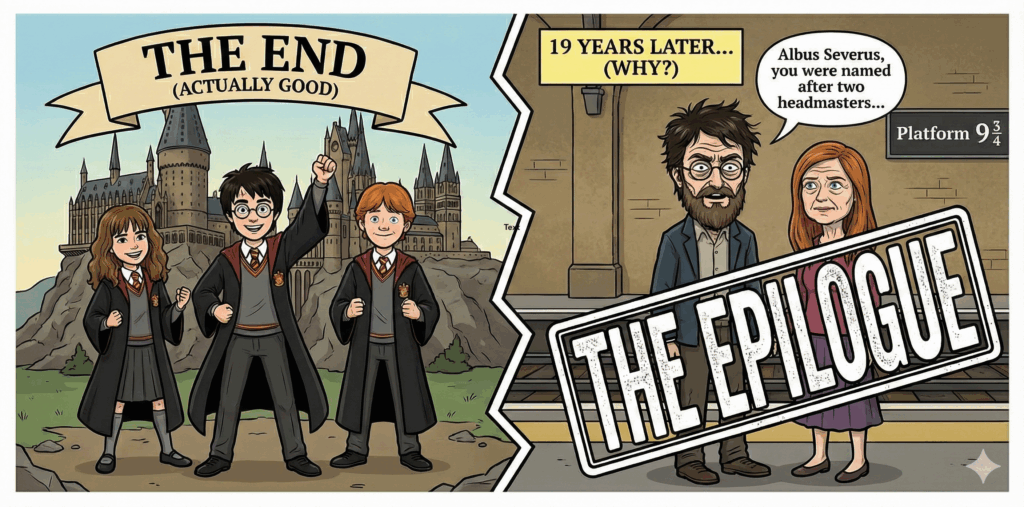

And then the epilogue happens.

And everything collapses like a poorly cast spell.

I have always hated the epilogue. I hated it when I read it. I hated it even more when I first saw it. This time it almost sent me into a dissociative state. I had flashbacks. I questioned my life choices. I checked the clock to see how long I had left on Earth.

Look. Epilogues are rarely a good idea. They are the narrative equivalent of a director leaning into the audience to whisper, “I do not trust you to understand closure.” Most stories do not need them. Some stories survive them. But the Harry Potter epilogue is the first one that actively ruins everything around it. It is the worst epilogue in the history of bad epilogues.

And it brings absolutely nothing to the table. Nothing. What do we learn? That Harry Potter is an objectively terrible father when it comes to naming his children. That is it. That is the entire thematic content. Albus Severus. Really. That child will spend his entire life explaining that his name is not a medical condition.

In the book, you can at least imagine everyone aging gracefully. Warm lighting. Subtle wrinkles. Dignity. Possibility.

The movie, however, said no. The movie said, “Let us attach latex to twenty year olds and hope for the best.” It looks like the makeup team googled “old person” and then slapped rubber onto the actors the way toddlers apply stickers. Everyone appears to be aging via slow dehydration. The uncanny valley has rarely been this flat and dusty.

But the real crime is how aggressively pointless it all is. The actual ending of the story is perfect. Evil defeated. World rebuilt. Characters changed. Narrative complete. That is an ending. That is closure. That is the moment you fade to black and roll credits.

The epilogue then bursts through the door uninvited and announces, “Surprise. Everyone became parents. Please clap.” It is like watching a movie reach a beautiful emotional crescendo and then immediately cut to someone asking if you have eaten enough vegetables today.

And please do not tell me it “shows life goes on.” The entire story already shows that. Life going on is the default state of humanity. You do not need to force the characters into middle age with names that sound like rejected Victorian baby books.

This epilogue does not deepen the story. It does not enrich the characters. It does not even provide satisfying fan service. It is just there. Lumbering around. Confused. Wrinkled in all the wrong places.

So here is my position, stated plainly. The Harry Potter epilogue is unnecessary, thematically hollow, visually cursed, dramatically limp, aggressively unhelpful, and absolutely the gold standard of how not to end a story. If epilogues across history gathered for a conference, this one would be the keynote speaker. It would arrive early, spill its coffee, and still get lost on the way to the podium.

If future Blu ray releases quietly removed it, I would consider that a public service.

And yes, I skipped it on my rewatch. Even I have standards.