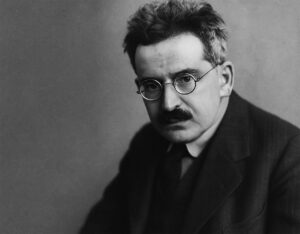

Walter Benjamin

I first read Walter Benjamin’s Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit at university, and the idea that stayed with me is his notion of Aura. Benjamin wrote that a work of art has a presence, a uniqueness that comes from existing in a specific place and time. Reproduction destroys that. Once something can be endlessly copied, the original loses part of what made it special.

The easiest way to understand this is to think about the Mona Lisa. If you see it on your phone, have you really seen it? Probably not. To see it, you have to go to the Louvre, push through a wall of selfie sticks, and realize that it’s surprisingly small. But still, standing there, you feel it — the strange gravity of the original, the weight of being in front of the thing itself. That’s what Benjamin meant by aura.

Mechanical reproduction changed that forever. And yet it also made new kinds of art possible. Without it, we wouldn’t have cinema, and without cinema, we wouldn’t have movie stars. The paradox is that the aura that disappeared from the artwork reappeared in the actor. Movie stars became the carriers of aura: distant, flawless, unreachable.

Then the tools of reproduction multiplied again, and suddenly everyone could reproduce themselves. The mystery of the movie star turned into the familiarity of the content (I use the word derogatory) creator. Distance was replaced by access. Cary Grant never posted about his morning routine; modern actors have entire teams curating theirs.

Every now and then, though, something resembling the old aura flickers back to life. The Barbie and Oppenheimer double feature or Deadpool & Wolverine, created what you could call event aura or to use another term FOMO. People didn’t just go to see the movies; they went to be part of them. The films became social events, something you could miss if you stayed home. It wasn’t the same as standing before the Mona Lisa, but it was similar in spirit — a reminder that presence still matters.

Still, the exception proves the rule. For most films, audiences have learned to wait. Why buy a ticket when the movie will stream in four weeks? You can experience it on your couch, pause for snacks, and, if you’re a YouTuber, record your “first reaction” video — complete with thumbnail face — for an audience that also waited. It’s the modern version of pilgrimage without ever leaving the house.

And that, I think, is the uncomfortable truth: we helped build this. We, the audience, chose convenience over presence. We turned the communal act of moviegoing into a content pipeline. When we complain that movies feel hollow, part of that emptiness comes from how we consume them.

Maybe Wayne’s World saw it coming. Back in 1992, two basement slackers with a public-access show were a joke about the absurdity of amateur broadcasting. Now that format is the culture. Replace the basement with a ring light, and Wayne and Garth are early YouTubers — the accidental prophets of the algorithm age. Benjamin argued that reproduction erodes aura. He was right, but the twist is that we finished the job ourselves. We didn’t just lose the aura; we traded it for comfort, access, and replayability. We don’t stand in front of the Mona Lisa anymore — we scroll past her, waiting for the reaction video to drop.